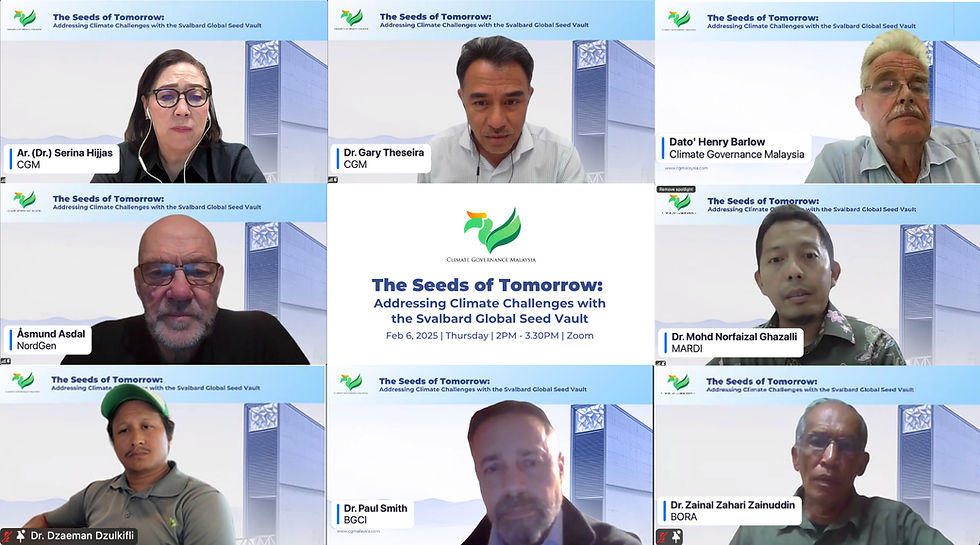

Opening Remarks by Ar. (Dr.) Serina Hijjas, Council Member, CGM

Keynote Address by Åsmund Asdal, Svalbard Global Seed Vault Coordinator, Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen)

Panel Discussion

● Dato’ Henry Barlow, Chair of the Board of Directors, CGM [Moderator];

● Dr. Paul Smith, Secretary General, Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI)

● Dr. Dzaeman B. Dzulkifli David, Executive Director, Tropical Rainforest Conservation and Research Centre (TRCRC)

● Dr. Mohd Norfaizal bin Ghazalli, Deputy Director, Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI)

● Dr. Zainal Zahari Zainuddin, Programme Director, Bringing Back Our Rare Animals (BORA)

Closing Remarks by Dr. Gary Theseira, Chair of the Council, CGM

Held on February 6, 2025, the webinar “The Seeds of Tomorrow: Addressing Climate Challenges with the Svalbard Global Seed Vault” provided a platform to explore the role of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and ongoing efforts to safeguard Southeast Asia’s rainforests.

In her opening remarks, Ar. (Dr.) Serina Hijjas, Council Member of CGM, brought attention to the alarming reality that humanity has exceeded six of the nine planetary boundaries—an outcome that could have been mitigated had we curbed greenhouse gas emissions and enforced the Kyoto Protocol. As climate change threatens the extinction of wild crop relatives— critical genetic resources for breeding pest-resistant and drought-tolerant crops—seed and gene banks have become essential in preserving the genetic diversity of endangered plant species.

Building on this, Åsmund Asdal, Svalbard Global Seed Vault Coordinator at the Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen), introduced the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Established in 2008 due to past seed losses in various gene banks, the vault serves as a secure repository for gene banks worldwide, storing duplicates of seeds free of charge while maintaining their ownership. Deposited seeds remain accessible only to the gene banks they originated from, ensuring availability for plant breeding and research while preventing privatization or patenting of genetic material. With the vault being symbolic with plant conservation, it is also used to raise public awareness about the importance of preserving genetic material.

Managed in partnership by the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Crop Trust, and NordGen, the vault operates under strict security and surveillance protocols. It currently houses over 1.3 million seed samples from more than 6,000 species, deposited by 123 institutions globally. All the seeds deposited in the vault are catalogued in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault Seed Portal, a publicly-accessible database. Malaysia’s participation began in May 2024, with the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) depositing rice seeds. A second deposit, including Oryza, Solanum, and Vigna species, is planned for February 2025.

He addressed a common misconception that rising Arctic temperatures could compromise the vault, which is buried in permafrost and maintained at -18°C. In reality, most of the cooling is artificial, with the surrounding permafrost providing a natural baseline of -3°C. This ensures a built-in safeguard, allowing the vault to remain operational even if artificial cooling systems require repair or replacement.

While the vault plays a crucial role in safeguarding agricultural biodiversity, its ability to store forest genetic resources remains limited. The facility is designed exclusively for orthodox seeds—those that can be dried and frozen for long-term conservation. Recalcitrant seeds, which cannot survive these storage conditions, are not accepted. Many forest tree species produce recalcitrant seeds, making them unsuitable for conservation in the vault. Additionally, tree species lack an international treaty equivalent to crop plants, which provides a set of rules for the conservation, use and exchange of plant genetic materials.

However, the distinction between plant and forest genetic materials can be blurry in areas with tropical trees and less industrialized agriculture. Some tree seeds are stored in the vault when gene banks classify them as plant genetic resources with agricultural significance. Agroforestry trees that contribute to intercropping, soil stabilization, fodder production, and fuelwood are often considered within the scope of plant genetic resources. The World Agroforestry Centre, for instance, has deposited nearly 2,000 accessions from 188 species, including Acacia and other multipurpose trees. The vault’s International Advisory Panel continues to evaluate the role of forest genetic resources in its mission and may consider expanding its scope in the future.

Åsmund highlighted a key example of the vault’s function when the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) withdrew over 100,000 seed samples following the Syrian civil war. These deposits allowed ICARDA to reestablish operations in Lebanon and Morocco, demonstrating the vault’s role as an active, living resource rather than a static “doomsday” facility.

Concluding his presentation, Åsmund outlined the vault’s operational processes, including the meticulous security checks and tracking systems ensuring the safe transport and storage of seeds. He reaffirmed the vault’s success, noting that in 17 years, not a single seed sample has been lost in transit, emphasising its reliability as a cornerstone of global biodiversity conservation.

Dato' Henry Barlow, Chair of the Board of Directors at CGM, echoed the vital role of the Svalbard Seed Vault in safeguarding global food security and set the stage for a panel discussion that explored Southeast Asia’s unique challenges. Preserving the region’s rich rainforest biodiversity is particularly complex, especially due to recalcitrant seeds—which comprise the majority of Southeast Asian rainforest species and cannot be frozen for long-term viability.

In the context of Malaysia, Dr. Mohd Norfaizal bin Ghazalli of the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) shared insights on the country’s national seed bank network, which houses a diverse collection of over 90,000 accessions, including rice, traditional vegetables, and rare fruits. While orthodox seeds can be stored in seed banks, recalcitrant seeds require field gene banks, which pose challenges due to resource-intensive maintenance. These efforts are supported by government agencies and international collaborations, such as the Crop Trust’s biodiversity initiative funded by Norway, enabling the preservation of critical genetic materials, including culturally significant rice varieties from indigenous communities. Additionally, research into cryopreservation for recalcitrant species, such as wild mangosteen and mangoes, aims to ensure the long-term protection of agro-biodiversity.

While Dr. Norfaizal’s discussion focused on agro-biodiversity, Dr. Paul Smith from Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) highlighted the urgent need to conserve Malaysia’s forest genetic resources, particularly its diverse tree species. Malaysia is home to 5,282 tree species, with 1,211 classified as threatened, yet 74% lack ex-situ conservation in gene banks or seed banks. Dipterocarps, keystone species in Malaysian forests, are particularly at risk, with 67% facing extinction and 64% absent from ex-situ conservation collections. Dr. Paul emphasized the critical need for in-situ conservation, highlighting BGCI’s Global Tree Assessment, which provides georeferenced data to guide conservation efforts—already being utilized in Sabah to designate high conservation value areas. Since many tropical species produce recalcitrant seeds, field gene banks are crucial for preserving genetic diversity. Additionally, BGCI has launched a Global Conservation Consortium for Dipterocarps, uniting 25 partner organizations across Southeast Asia to establish genetically diverse field gene banks, ensuring long-term resilience and restoration potential for these critical forest species.

Continuing Dr. Paul’s discussion, Dr. Dzaeman Dzulkifli from the Tropical Rainforest Conservation and Research Centre (TRCRC) emphasized the critical role of living collections and field gene banks in safeguarding Malaysia’s tree species. Given the country’s diverse microclimates and terrains, TRCRC has established large-scale field gene banks across Sabah, Perak, and even urban areas, including airports. Recognizing the challenges posed by dipterocarp seed viability—where seeds germinate rapidly and fruiting occurs only every five to seven years—TRCRC has developed protocols for tracking phenology, prioritizing species, and mobilizing local communities for seed collection, an approach successfully tested during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, the focus is on scaling up restoration efforts through digital tools that streamline data collection and ensure species are restored in the right ecosystems. Beyond conservation, these efforts enhance biodiversity, protect watersheds, and contribute to carbon sequestration, reinforcing the need for scientifically guided, cost-effective restoration strategies.

Elaborating on the restoration aspect, Dr. Zainal Zahari Zainuddin from Bringing Back Our Rare Animals (BORA) highlighted the vital role of Ficus species in habitat restoration. As a keystone species, Ficus provides essential food sources for diverse fauna, including orangutans, hornbills, gibbons, elephants, and bearded pigs. Their fast growth, frequent fruiting, and adaptability make them ideal for restoration. At the Sabah Ficus Germplasm Centre, a dedicated team manages a living collection of 95 Ficus species, preserving seeds of around 45 species in an ultra-cold freezer (-82°C) for future use. Since 2019, BORA has collaborated with major plantations to restore 165 hectares with 8,500 fig trees and other native species, overcoming challenges such as variable soil conditions, weather, and wildlife interference. Through continuous research and monitoring, BORA refines its restoration approach, ensuring long-term biodiversity conservation and ecosystem resilience.

Dr. Gary Theseira, Chair of the Council at CGM, concluded the webinar by emphasizing the crucial role of plants in sustaining human civilization and ecosystems, reinforcing the importance of preserving genetic resources, managing seed banks, and restoring habitats as outlined by the speakers. As a mega-biodiverse nation, Malaysia must prioritize biodiversity conservation to safeguard long-term ecological and economic resilience while fostering global collaboration in protecting natural ecosystems.

.png)

Comments